The Craft of Research

stack

stack

Research, Researchers, and Readers

Prologue: Becoming a Researcher

Thinking in Print: The Uses of Research, Public and Private

What is Research?

In the broadest terms, we do research whenever we gather information to answer a question that solves a problem.

A distinction needs to be made between a question and a problem.

Why Write it?

- Write to Remember

- Write to understand

- Write to Test Your Thinking

We write to remember more accurately, understand better, and evaluate what we think more objectively.

Why a Formal Paper?

Writing a paper is like writing a front-end that needs to follow the HTTP protocol so that it is easier to parse.

Writing is Thinking

Writing up your research is, finally, thinking with and for your readers.

Not only for satisfying one’s teacher.

Find a topic that you care about, and ask a question that you want to answer.

Also,

Some of the world’s most important research has been done by those who persevered in the face of indifference or even hostility because they never lost faith in their vision.

So how to balance your belief in the worth of your project with the need to accommodate the demands of teachers and colleagues is important.

Connecting with Your Reader: Creating a Role for Yourself and Your Readers

When you read a book or scientific paper, you silently converse with its writers.

Conversing with Your Readers

Writing is an imagined conversation. Once we decide what role to play and what role to assign our readers, those roles are fixed.

Understanding Your Role

-

I’ve found some new and interesting information(Bilibili)

-

I’ve Found a Solution to an pmportant practical problem(Blog)

-

I’ve Found an Answer to an Important Question(Publication)

Imagining Your Readers’ Role

- Entertain me(Appealing)

- Help me solve my practical problem(Andrew Ng ML courses)

- Help me understand something better(Not only discovery but also the vision of the future, for readers of the paper)

Expect you to be objective, rigorously logical, and able to examine everything from all sides.

A list of questions to be answered…

Asking Questions, Finding Answers

From Topics to Questions

Refine it to a manage scope, then question it to find the makings of a problem that can guide your research.

If you are new to research, the freedom to pick your own topic can seem daunting.

Several definitions:

- Subject: broad area of knowledge

- Topic: a specific interest within that area

A topic is an approach to a subject, one that asks a question whose answer solves a problem that your readers care about.

Question or Problem?

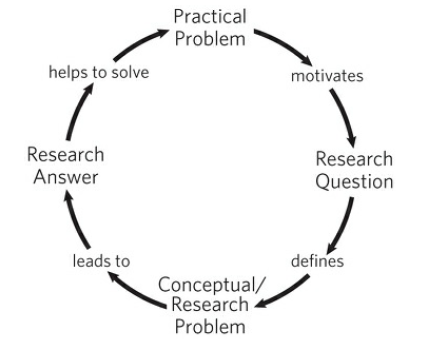

A question leads to a problem(trouble which researchers reach a consensus that is significant)

From an Interest to a Topic

Motivations for tech field:

- Build a new mechanism

- Faster

- Cheaper

- Safer

From a Broad Topic to a Focused One

Counter-Example:

Free will in Tolstoy -> The conflict of free will and inevitability

The history of commercial aviation -> The contribution of the military in developing the DC-4

Note what happens when we restate static topics as full sentences. There is nothing worth arguing about the above points

From a Focused Topic to Questions

Articles without reviews -> Became a problem -> It would be valuable to write a review

The Most Significant Question: so What?⭐

Once you have a question that holds your interest, you must pose a tougher one about it: So what?

Step1: Name Your Topic

I am trying to learn about/working on/studying …

Step2 : Add an Indirect Questions

because I want to find out who/what/when/where/whether/why/how

Step 3: Answer So What? by Motivating Your Question

in order to help my reader understand

However,

You may begin your research without a good answer to that third question-Why does this matter?

Figure out and then begin to write.

Quick Tip: Finding Topics

Internet can be relied for AI.

Don’t try to answer general or big problems.

Focus on small problems discovered while taking internship.

From Questions to a Problem

Figure out the alternative way for the academia.

- Topic

- Question

- Significance

- Question

When you move to step 3, strong relationship with readers are established.

At that point, you have posed a problem that they recognize needs a solution.

Understanding Research Problems

Practical Problems: What Should We Do?

Make a task more accurate in a certain data set or make the algorithm run faster.

Mostly for tech

Conceptual Problems: What Should We Think?

Mostly for science

The relationship between practical and conceptual problems are below?

Focus, or

I don’t see the point here, this is just a data dump

Understanding the Common Structure of Problems

Same two-part structure:

- a situation or condition

- undesirable consequences caused by that condition

The Nature of Practical Problems

Find out the cost readers pay

- The ozone layer is thinning

- A thinner ozone layer exposes us to more ultraviolet light

- Too much ultraviolet light can cause skin cancer

The Nature of Conceptual Problems

Highlight the more important issues that would be obscured by this

- The answer to Q1 helps you answer Q2

- The answer to Q2 is more important than the answer to Q1

If you will still end up being asked SO WHAT, then you are not the target user. Hooray for curiosity!

Distinguishing “Pure” and “Applied” Research

Satisfying curiosity or reducing costs?

Connecting Research to Practical Consequences

Connecting to applied area is also a great approach.

- Topic

- Question

- Significance

- Potential Practical Application

- Significance

- Question

Finding a Good Research Problem

- Communicate

- Read

- Look at your own conclusion

Learning to Work with Problems

- Will readers think it should be solved?(else I don’t care)

- Can I solve it?

Quick Tip: Manage the Unavoidable Problem of Inexperience

Some suggestions:

- Know that uncertainty and anxiety are natural and inevitable

- Get control over your topic by writing about it along the way(workshop)

- Break the task into manageable steps and know that they are mutually supportive

- If you are a student, count on your teachers to understand your struggles

- Set realistic goals

- Most important, recognize the struggle for what it is-a learning experience

Keep communicating with your readers and users

From Problems to Sources

Simply find paper by Depth-First-Search forward and backward is enough.

Engaging Sources

Identify by two factors:

- Citation(for old papers)

- Ranking(somewhat subjective, and most likely the conference you cite the most is the one you posted)

Making an Argument

Prologue: Assembling a Research Argument

You can’t wait to plan your argument until after you’ve gathered every last bit of data and found every last relevant source.

Mostly exploring the unknown

Only when you try to make a research argument that answers your reader’s predictable questions can you see what research you have yet to do.

-

Aims not at coercing each other into agreement, but at cooperatively finding the best answer to an important but challenging question.

-

Support our claims with good reasons and evidence(Why should I believe that?)

Making Good Arguments

Argument As a Conversation with Readers

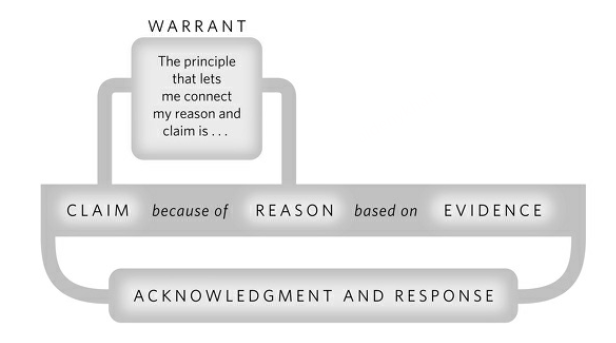

A claim, back with reasons supported by evidence, acknowledge and respond to other views, and sometimes explain your principles of reasoning.

- Claim

- Reasons

- Evidence

- Acknowledgement and Response

- Warrant

Supporting Your Claim

- Support claims with reasons

- Base reasons on evidence(root)

Acknowledging and Responding to Anticipated Questions and Objections

Reach out to potential concern

The challenge all researchers face, however, is not just responding to readers’ questions, alternatives, and objections, but imagining them in the first place.

Connecting Claims and Reasons with Warrants

Offer a general principle

Building a Complex Argument out of Simple Ones

Five basic elements

Creating An Ethos by Thickening Your Argument

The ultimate goal

Quick Tip: A Common Mistake-Falling Back on What You Know

- Rely too heavily on what feels familiar(inexperienced)

- Rely on ways of arguing that are familiar to you from your education or experience(new to a field)

- Oversimplify in a different way(familiar with your field)

Making Claims

- What kind of claim should I make?

- Is it specific enough?

- Will my readers think it is significant enough to need an argument supporting it?

Determining the Kind of Claim You Should Make

Making Conceptual Claims:

- Claims of fact or existence

- Claims of definition and classification

- Claims of cause and consequence

- Claims of evaluation or appraisal

- Claims of action or policy

Making Practical Claims:

- Why your solution is feasible; how it can be implemented with reasonable time and effort

- Why it will cost less to implement than the cost of the problem

- Why it will not create a bigger problem than the one it solves

- Why it is cheaper or faster than alternative solutions-a claim often difficult to support

Evaluating Your Claim

Make your claim specific with precise language

Make your claim significant(if readers accept a claim, how many other beliefs must they change?)

- Plot all the data

- Use the data to answer existing problems

- Consider opposite claims

Qualifying Claims to Enhance Your Credibility

-

Acknowledge limiting conditions

-

Use hedges to limit certainty(all, no one, every, always, never should be avoided)

Assembling Reasons and Evidence

Judge the logic -> look at the evidence

You must offer readers a plausible set of reasons, in a clear, logical order, based on evidence they will accept. This chapter shows you how to do that.

Using Reasons to Plan Your Argument

Introductory claim+reason(evidence)+conclusion

Distinguishing Evidence from Reasons

Costs of higher education ↑ so some students leave college with a crushing debt burden

to

In 2013, nearly 70 percent of students … with loans averaging $30000

Distinguishing Evidence from Reports of It

- Data you take from source have invariably been shaped by that source

- Cannot avoid manipulating them once again, at least by putting them in a new content

Evaluating Your Evidence

-

Report evidence accurately(record the data completely and clearly)

-

Be appropriate precise(watch for words like some,most,many,almost,often,usually,frequently,generally, also avoid being too precise)

-

Provide sufficient, representative evidence(with one quotation, one number, one personal experience)

-

Consider the weight of authority(evidence from Wikipedia will not be accepted)

Acknowledgements and Responses

Anticipate, acknowledge, and respond to questions, objections, and alternatives.

- Intrinsic soundness

- Extrinsic soundness

Questioning Your Argument as Your Readers Will

Share the core of your argument with a friend, mentor, or colleague you trust, do it.

Some possible questions:

- Why do you think there’s a problem at all?

- Have you properly defined the problem?

Evidence may also be challenged.

Imagining Alternatives to Your Argument

Deciding What to Acknowledge

- Choosing what to respond to

- plausible charges of weaknesses that you can rebut

- alternative lines of argument important in your field

- alternative conclusions that readers want to be true

- alternative evidence that readers know

- important counterexamples that you have to address

- Acknowledgement flaws in your argument

- the rest of your argument more than balances the flaw

- while the flaw is serious, more research will show a way around it

- while the flaw makes it impossible to accept your claim fully, your argument offers important insight into the question and suggests what a better answer would need

- Acknowledgement questions you can’t answer

Framing Your Responses as Subordinate Arguments

The Vocabulary of Acknowledgement and Response

- Acknowledging objections and alternatives

- Responding to objections and alternatives

Quick Tip: Three Predictable Disagreements

- There are causes in addition to the one you claim

- What about these counterexamples?

- I don’t define X as you do. To me, X means …

Warrants

Warrants in Everyday Reasoning

Warrants are general principles that connect reasons to claims.

Consisting of two parts:

- A general circumstance that lets us draw a conclusion about

- A general consequence

Testing Warrants

Five questions to answer:

- Is that warrant reasonable?

- Is it sufficiently limited?

- Is it superior to any competing warrants?

- Is it appropriate to this field?

- Is it able to cover the reason and claim?

Knowing When to State a Warrant

- Your readers are outside your field.

- You use a principle of reasoning that is new or controversial in your field.

- You make a claim that readers will resist because they just don’t want it to be true.

Quick Tip: Reasons, Evidence, and Warrants

Justify your reasons in two ways: by offering evidence to support them or by deriving them from a warrant.